EU Legislation Affecting Supply Chain Management (Part 2)

The French Law on the Duty of Vigilance of Parent and Instructing Companies (2017) effective in early 2018 provides a reference point on the law itself and its reach and informs how this is being used to structure and inform wider EU directives and legislation.

The guidance is divided into two parts:

-

The first part relates to the “cross-cutting principles” such as the content, scope and perimeter of the obligation, which must constantly guide companies" conduct in the exercise of the duty of vigilance. These principles should therefore be kept in mind and integrated into company plans.

-

The second part deals more specifically with the five measures announced by the Law (see below), it being specified that these measures are neither restrictive nor exclusive. The Law also provides that they may be supplemented by any further or amending decree that may be made subsequent to the act itself. Further, the expectation is that a company should take any additional measures necessary to meet its general duty of vigilance, namely the identification of risks and the prevention of severe impacts on human rights, the environment, health and safety of persons in its value chain.

Of significant importance is the drafting authors’ deliberate choice not to talk about “best practices”, but the quality of vigilance measures implemented for each company on its particular operating circumstances.

The implementable five measures are:

-

A risk mapping meant for their identification, analysis and prioritization.

-

Regular evaluation procedures regarding the situation of subsidiaries, subcontractors or suppliers with whom there is an established commercial relationship, in line with the risk mapping.

-

Appropriate actions to mitigate risks or prevent severe impacts.

-

An alert mechanism for the existence or materialization of risks, established in consultation with the trade unions considered as representative within the said company.

-

A system for monitoring the measures implemented and evaluating their effectiveness.

From the point of view the principles we can see there are six primary areas:

-

Normative content of the duty of vigilance

-

Company liable for the obligation of vigilance

-

Organizational perimeter of the obligation of vigilance: companies on which vigilance must be exercised

-

Substantial perimeter of the obligation of vigilance: impacts on which vigilance must be exercised

-

Temporal perimeter of the duty of vigilance: when to be vigilant

-

Interpersonal perimeter of the duty of vigilance: persons taking part in the duty of vigilance.

The impact of the legislation concerns all French headquartered entities and whilst it covers effectively the top 1% of companies, due to the size of company it captures the cascade down through the supply/value chain becomes quite extensive. I have chosen not to try and summarize the Articles applicable as they are complex and quite extensive as you can see set out below:

JORF n ° 0074 from March 28, 2017 - text n ° 1

LAW n ° 2017-399 of March 27th, 2017 on the duty of vigilance for parent and instructing companies

Article 1

After article L. 225-102-3 of the Commercial Code [Code de commerce], an article L. 225-102-4 is inserted and reads as follows:

"Art. L. 225-102-4.-I.-Any company that employs, by the end of two consecutive financial years, at least five thousand employees itself and in its direct or indirect subsidiaries whose registered office is located within the French territory, or at least ten thousand employees itself and in its direct or indirect subsidiaries whose registered office is located within the French territory or abroad, shall establish and effectively implement a vigilance plan.

"Subsidiaries or controlled companies that exceed the thresholds referred to in the first paragraph shall be deemed to satisfy the obligations provided in this article, if the company that controls them, within the meaning of

Article L. 233-3 of the French Commercial Code, establishes and implements a vigilance plan covering the activities of the company and of all the subsidiaries or companies it controls. "The plan shall include reasonable vigilance measures adequate to identify risks and to prevent severe impacts on human rights and fundamental freedoms, on the health and safety of individuals and on the environment, resulting from the activities of the company and of those companies it controls within the meaning of II of article L. 233-16, directly or indirectly, as well as the activities of subcontractors or suppliers with whom they have an established commercial relationship, when these activities are related to this relationship.”

"The plan is meant to be drawn up in conjunction with the stakeholders of the company, where appropriate as part of multi-stakeholder initiatives within sectors or at territorial level. It includes the following measures:

"1° A risk mapping meant for their identification, analysis and prioritization;

"2° Regular evaluation procedures regarding the situation of subsidiaries, subcontractors or suppliers with whom there is an established commercial relationship, in line with the risk mapping;

"3° Appropriate actions to mitigate risks or prevent severe impacts;

"4° An alert and complaint mechanism relating to the existence or realization of risks, drawn up in consultation with the representative trade union organizations within the company;

"5° A system monitoring implementation measures and evaluating their effectiveness.

Annexes

"The vigilance plan and the report concerning its effective implementation shall be published and included in the report mentioned in article L. 225-102.

"A decree issued by the Conseil d'Etat may expand on the vigilance measures provided for in points 1 to 5 of this article. It may detail the methods for drawing up and implementing the vigilance plan, where appropriate in the context of multi-stakeholder initiatives within sectors or at territorial level.

"II.-When a company receiving a formal notice to comply with the obligations laid down in paragraph I, does not satisfy its obligations within three months of the formal notice, the competent court may, at the request of any party with standing, order the company, including under a periodic penalty payment, to respect them.

"The case may also be referred for the same purpose to the president of the court in the context of summary proceedings.

Article 2

After the same article L. 225-102-3, it is inserted an article L. 225-102-5 and reads as follows:

"Art. 225-102-5.-Following the conditions provided in articles 1240 and 1241 of the Civil Code, a breach of the obligations defined in article L. 225-102-4 of this Code, establishes the liability of the offender and requires him to remedy any damage that the execution of these obligations could have prevented.

"The civil liability action is brought before the competent court by any person proving standing.

"The court may order the publication, dissemination or display of its decision or an extract thereof, according to the terms it specifies. The costs are borne by the person found liable.

"The court may order the execution of its decision under a periodic penalty payment."

Article 3

Articles L. 225-102-4 and L. 225-102-5 of the Commercial Code apply from the report mentioned in article L. 225-102 of the same code, relating to the first financial year opened after the publication of this Law. By way of derogation from the first paragraph of this article, for the financial year during which this Law was published, paragraph I of article L. 225-102-4 of the said Code applies, with the exception of the report in its penultimate paragraph.

This Law shall be executed as the law of the State.

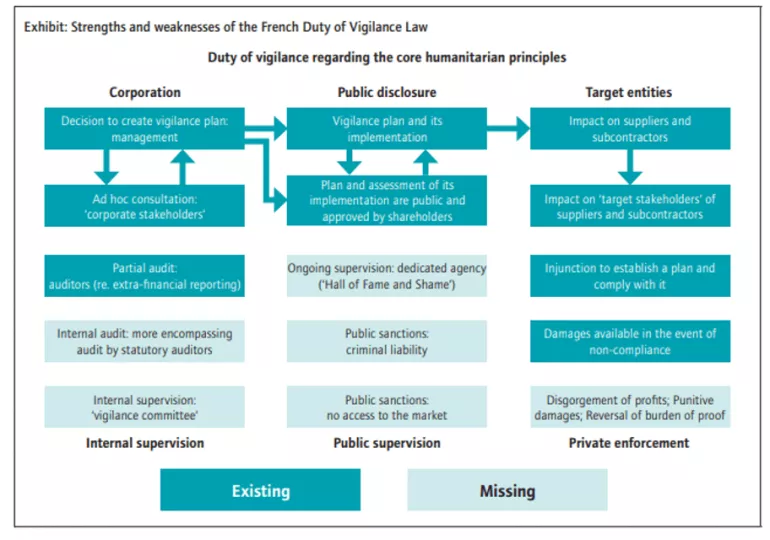

However, it is widely recognized that the French vigilance Law had some shortcomings as well as strengths that require companies to act properly and not just simply report! Therefore, there has been a consensus on four additional sanctions that are needed, namely:

-

Criminal sanctions for the most flagrant violations of the law, such as the lack of an established plan or monitoring process, or gross or willful misrepresentation in the plan or the report on its implementation.

-

Disgorgement of profits made by the company through suppliers and subcontractors which are not compliant with the core humanitarian principles.

-

Punitive damages in the event of gross or willful violation by the company of its duty of vigilance.

-

Exclusion of access to the EU market for suppliers and contractors found to violate the core humanitarian principles.

Accordingly, this all feeds into the current dialogue and considerations within the EU in drafting the proposed new legislations that we can reasonably expect to be instituted in the next 12-18 months to supplement and extend the French Law of Vigilance and hence its catalytic role in the development of legislation. This was well summarized in the Etui Policy Brief referenced in the foot of this note.

In summary of all the activity the following six recommendations are expected to be adopted:

-

Core mechanism: Companies should adopt and apply vigilance plans designed to enforce core humanitarian principles throughout the production cycle, including in subsidiaries, suppliers and subcontractors. Core humanitarian principles should cover human rights and fundamental freedoms (including trade union and workers’ rights), health and safety, and the environment.

-

Scope: The directive should apply to companies whose seat is in the EU as well as companies above a certain size threshold selling goods and services within the EU. A specific and much more simplified regime should be applicable to SMEs.

-

Duty: The duty of vigilance should go beyond a mere due diligence obligation. The ‘vigilance plan’ should mandate reasonable but adequate measures not only to identify risks but also to monitor them and to mitigate and prevent severe violations of core humanitarian principles.

-

Internal supervision: Auditors should be involved in the process. Stakeholders, including trade unions and worker representatives, must be proactively involved in shaping and monitoring the vigilance plan: an internal ‘vigilance committee’ should be set up to prepare the vigilance plan and monitor its implementation. This committee should be independent by design and be provided with the appropriate legal and financial means to carry out its duties. An alert mechanism must also be set up in the company.

-

Public supervision: A public supervisory agency should be set up to adopt standards, promote good practices, enforce the rules, and accredit processes for the establishment of blacklists and whitelists of suppliers and contractors.

-

Liability and enforcement: Companies should be accountable for the impacts of their operations. Liability must be introduced for cases where companies fail to respect their due diligence obligations, without prejudice to joint and several liability frameworks. A proper enforcement mechanism would need to include criminal sanctions, disgorgement of profits, punitive damages, and exclusion of access to the EU market for suppliers and contractors found to violate the core humanitarian principles, as well as the ability for the courts to reverse the burden of proof in certain cases. Finally, effective remedies and access to justice should be available for victims, including trade unions.

The European Commission published its proposed, long-awaited and potentially highly significant directive on due diligence on 23 February 2022. The directive will impose a duty on major businesses to carry out human rights and environmental due diligence in their global value chains.

Although mainly aimed at EU businesses, the directive will also affect UK and other non-EU businesses which either have sufficiently large EU activities, have EU parents or are involved in EU supply chains. The costs involved may be significant.

Who does it apply to?

The directive applies to companies and some other legal entities, such as credit institutions, insurance companies and some pension funds. It covers three groups, starting with EU entities with more than 500 employees and a net worldwide turnover of more than €150 million.

Second are EU entities with more than 250 employees and a net worldwide turnover of more than €40 million, if half or more of their turnover comes from certain ‘high impact’ sectors. These include the manufacture and wholesale trade of textiles and leather, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, food manufacture, mineral resource extraction and wholesale trade and manufacture of metal and other mineral products.

Finally come non-EU entities which generate a net turnover of more than €150 million in the EU or between €40 million and €150 million in the EU with at least half coming from the high impact sectors. This means that companies registered in England and Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland must meet the directive requirements if they satisfy this test.

What does it require?

Companies covered by the directive must identify actual and potential adverse human rights violations and environmental impacts from their operations and supply chains, including established relationships with contractors, subcontractors, and partners.

Adverse impacts cover, for example, human rights issues such as inadequate workplace health and safety and child labour and environmental impacts such as loss of endangered species and greenhouse gas emissions.

Financial services must identify adverse impacts before providing credit, loan or other financial services. Where relevant, entities must consult potentially affected groups such as workers and other stakeholders.

Companies must also take appropriate measures to prevent or mitigate identified impacts. This includes having a prevention action plan with timelines for action, indicators to measure improvements, and measures to end or minimize adverse impacts. They must monitor the effectiveness of their operations and measures once a year, update their policy and report annually on what they have done.

Affected companies must have a due diligence policy which sets out their approach, with the processes and measures to be taken, and a code of conduct for employees and subsidiaries. The policy must be updated annually and be integrated into other corporate policies.

EU and non-EU entities with a turnover of more than €150 million must also make their business model and strategy compatible with transitioning to a sustainable economy and limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius, in line with the Paris Agreement. They must identify climate change risks and impacts and include emission reduction objectives.

To reinforce the general approach, directors of EU companies will also be personally responsible for putting the various due diligence actions in place and considering relevant input from stakeholders and civil society organisations. They must also ensure the corporate strategy takes account of the adverse impacts identified and the measures taken to prevent or end them.

When things go wrong

Member states will have to establish supervisory authorities to make sure entities comply. Non-EU companies will be supervised by the authority in the member state where they have a branch or where most of their relevant net turnover is generated.

Businesses must have a complaints procedure where trade unions, civil society organisations and anyone affected by an adverse impact can raise concerns about adverse human rights and environmental impacts. Businesses may face fines imposed by a national authority based on turnover as well as civil liability.

How significant is the change?

Some, particularly larger, companies already use value chain due diligence voluntarily to meet international standards. Although the UK is moving to greater disclosure of sustainability-related information in companies’ accounts, it is not yet mandating due diligence exercises or requiring plans to remove or reduce adverse impacts.

The turnover criteria mean the directive is expected to apply directly to only around 1% of companies in the EU. Some have criticized the proposal for not covering enough companies and not going far enough. However, small and medium enterprises could be indirectly affected, for example if they have an established relationship with a larger business.

Indeed, a similar French regime has already led to around 80% of French companies having to implement at least some due diligence measures because they supply larger companies.

This is where the largest impact on UK business is likely to arise. UK subsidiaries of EU affected companies will need a code of conduct and to identify actual and potential adverse human rights and environmental impacts to feed into their group policy. UK businesses who have established business relationships with affected EU entities will also need to do this.

Fulfilling the obligations under the Directive may not be straightforward for UK and EU companies. Each member state will implement the Directive slightly differently and could impose higher standards. Further, each affected company will have a slightly different approach in what it asks its suppliers to do. So, a company that supplies a number of different EU companies and/or is a subsidiary of an EU company could face varying requirements with the associated cost implications.

This is the first time the EU has proposed changes in the sensitive area of directors’ duties. ecoDA, the umbrella organization representing national institutes of directors in Europe is not impressed, complaining the proposal is ‘unclear and unprecise’ on directors’ duties.

Although the directive may change before it is finally adopted, because of the significant change it will bring UK businesses need to start now to work out how they will be affected and what the EU businesses they work with are planning.

Commentary from the WEF White Paper: Supply Chain Sustainability Practices: State of Play – May 2022 (WEF_Supply_Chain_Sustainability_Policies_2022.pdf (weforum.org) summarised the position as follows:

Source: European Commission, Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937, 23 February 2022.

A few other key takeaways were as follows:

-

The implementation guidance from the Financial Stability Board (FSB)-led Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was revised in October 2021 to encourage the disclosure of Scope 3 emissions – those stemming from a company’s value chain – subject to materiality. 2021-TCFD-Implementing_Guidance.pdf (bbhub.io)

-

EU to propose the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which would impose a carbon price on imports across six sectors equivalent to the level paid within the single market. Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (europa.eu)

-

A combination of technologies will be necessary, as there is no silver bullet:

-

Technology plays an important role in supply chain visibility and traceability. World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

-

OECD sectoral due diligence Various processes have led to specific, non-binding due diligence guidance for the following supply chains: conflict minerals (2011, subsequent revisions); child labour in minerals (2017); garment and footwear (2017); agriculture (2016); extractives (2017); and the financial sector (2019).

-

EU Circular Economy Action Plan Adopted 2020, action ongoing EU Legislative and non-legislative measures 35 listed actions to ensure products sold in the EU are better designed for circularity and that waste is prevented. Focus sectors include electronics, batteries and vehicles, packaging, plastics, textiles, construction and buildings, food, water and nutrients. A recent proposal includes a Regulation on Ecodesign for Sustainable Products that would outline requirements for products to be easier to reuse, refurbish, repair and recycle. Regulated products will need to have digital product passports to track substances of concern across the supply chain

-

Regulation to minimize EU-driven deforestation and forest degradation Proposed in November 2021 EU Binding EU-wide legislation Mandatory due diligence rules for businesses that deal in specific commodities in the EU (soy, beef, palm oil, wood, cacao and coffee, as well as some derived products); obligations will vary based on the country or region of production.

-

Japan guide on environmental due diligence 2020 Japan Guidance Provides guidance for environmental due diligence along the value chain, aligned with OECD standards.

-

UK Plastic Packaging Tax 2021, in effect from 1 April 2022 UK Tax A tax of £200 per tonne on plastic packaging manufactured in or imported into the UK containing less than 30% recycled plastic. Manufacturers and importers of less than 10 tonnes of plastic packaging per year are exempted.

Meanwhile, The Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act which was adopted in 2019 by the Dutch Senate will become effective shortly (date to eb announced). However, in order for companies to prepare and fully investigate their supply chains, it is not expected to come into effect until mid-2022. The law obliges companies to examine whether their goods or services have been produced with child labour, and if so, mitigate and prevent child labour in their supply chain.

Who is concerned?

The Act applies to all companies selling or supplying goods or services to Dutch consumers, no matter where it is based or registered, with no exemptions for legal form or size. The Act primarily focuses on Dutch and foreign companies that consistently do business with Dutch consumers, not unregistered foreign companies that sell goods or services less than twice in a calendar year.

Requirements

Under the Act, firms are required to conduct the following in order to exercise due diligence:

-

Investigate their supply chains to identify any suspicion of child labour

-

Draft and implement a plan of action to terminate child labour if identified from investigation

-

Create an action plan to avoid the use of child labour

-

Submit a declaration to the yet-to-be-determined regulatory body, affirming that they have exercised an appropriate level of supply chain due diligence in order to prevent child labour

Companies will have six months from the Law's effective date to submit the required documentation demonstrating compliance with the statute.

Consequences

Non-compliance with the Act will be overseen through complaints with offending companies by victims, consumers and other stakeholders. That is, no active investigations will be conducted by the regulator. If sufficient evidence is presented, the regulator can determine that a violation of the law has been made by the company and provide a legally binding course of action. Therefore, it is one of the first criminal enforcement tools in the field of business and human rights.

There are significant administrative fines and criminal penalties for non-compliance:

-

Fines for failing to file a declaration from €4,350 upwards.

-

Companies that fail to comply can be subject to fines of up to €870,000 or 10% of total global revenue

-

If a company receives two fines within five years, the responsible company director is liable for up to two years of imprisonment under the Economic Offences Act

-

Penalties increase exponentially for companies found to have inadequate due diligence or lack of an appropriate plan of action to detect and prevent the use of child labour

Risk Mitigation

In order to mitigate the risk of penalties and fines, companies need to develop a comprehensive supply chain profile, to understand the entirety of the supply chain, from raw materials to finished goods.

Finally, From July 1, 2022, the Norwegian Transparency Act will impose extensive new due diligence obligations on large companies selling products and services in Norway. The legislation mandates that liable firms be able to account for the human rights and fair labour practices, not only of direct or “Tier 1” suppliers, but of all those indirect vendors and subcontractors who comprise the entirety of the upstream and downstream value chain.

These developments make clear that, in Europe, the era of voluntary, self-regulation in respect of social and environmental due diligence has come to a decisive end. The new Norwegian Transparency Act ("Åpenhetsloven"), adopted formally by the Norwegian parliament in June 2021, is about to become part of an increasingly complex ecosystem of due diligence regulation spreading across the EU and globally.

However, the Norwegian law is distinguished from, for instance, the recently-introduced German Supply Chain Act, by the fact that it imposes due diligence obligations across all tiers of the supply base. This means that liable firms will need to extend their due diligence to the labour and human rights practices, not only of their direct or “Tier 1” suppliers, but of all those Tier 2, Tier 3, etc. suppliers that constitute the upstream value chain. As research has consistently shown this is where the majority of both poor visibility and risks lies at about 70-80% in total supply chain context. The Norwegian regulation is, therefore, significantly more stringent than many comparable due diligence regimes operational elsewhere in Europe and consequently presents a much greater compliance challenge for reporting companies.

The legislation will apply to all companies registered in Norway, and foreign companies selling in Norway, that meet at least two of the following three criteria:

-

At least 50 full-time employees (or equivalent annual man-hours)

-

An annual turnover of at least NOK 70 million (€6.9 million, or US $7.94 million)

-

A balance sheet sum of at least NOK 35 million (€3.5 million, or US $3.97 million).

To put these figures into context, the EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) applies to companies with more than 500 employees, and while the forthcoming Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will reduce that figure to 250, it remains five-times higher than the reporting threshold mandated by the Norwegian Act. Similarly, the due diligence obligations set out under the German Supply Chain Act will apply initially to companies with at least 3,000 employees, a figure that will reduce to 1,000 from January 2024.

It is clear, therefore, that many of the companies covered by the Norwegian Transparency Act will be subject to due diligence and reporting requirements for the first time and are more liable, therefore, to lack the data and explicit mapping of their supply chains to comply fully to ensure compliance.

Drawing on OECD guidelines, the Norwegian Transparency Act obliges companies to conduct human rights and “decent working conditions'' due diligence activities on both their internal operations and those of their suppliers. Critically, the legislation also stipulates an expansive definition of “suppliers” as “any party in the chain of suppliers and subcontractors that supplies or produces goods, services or other input factors included in an enterprise's delivery of services or production of goods from the raw material stage to a finished product.” In practice, this means that firms will need to adopt measures to identify potential and actual violations of human rights or decent working conditions in their supply base and implement mechanisms to cease, prevent or mitigate such infringements where they do occur. This is very similar and a parallel of the French Vigilance Law enacted in 2017 and set to be augmented by further EU directives as discussed earlier in this note.

Companies will, furthermore, be obliged to transparently report on due diligence processes and findings. This includes publishing, by 30 June each year, an annual account of due diligence practices and findings to an easily accessible location, such as on a company website. Businesses will also be compelled to respond, within a “reasonable” timeframe, to written information requests from members of the public regarding its handling of specific labour or human rights due diligence matters. Which will clearly be of interest to investors and companies contemplating providing goods and services as there will of course be reputational association should companies not be compliant in this area.

The Norwegian Consumer Authority is responsible for overseeing and enforcing the Act. In the event of a violation, the Consumer Authority may issue an order requiring or enjoining compliance, or it may issue a fine.

This summary, yes it is a summary combines al the current intelligence gathered to the End of May 2022 and will of course be updated as we progress through the year.

As ever the complexity and diversity of regulation of global/international business continues to grow and dictates that sound and accessible data through well-structured systems is no longer an option but a necessity for medium to large enterprises to allow them to compete and remain compliant.

Resources:

2019-VPRG-English.pdf (vigilance-plan.org)

Policy Brief-EEESPolicy-N°1-V5.indd (etui.org)

European Parliament (europa.eu)

G20 Countries | Global Slavery Index

Corporate sustainability due diligence (europa.eu)

Value chain and supply chain sustainability | The Carbon Trust

Questions and Answers: Just and sustainable economy (europa.eu)

EU taxonomy for sustainable activities | European Commission (europa.eu)

The EU’s Public Procurement Framework (europa.eu)

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0024

Responsible Business Alliance, “Code of Conduct”: https://www.responsiblebusiness.org/code-of-conduct/

Smelters & Refiners Lists (responsiblemineralsinitiative.org)

GLOBAL PRODUCT CARBON FOOTPRINT CALCULATION AND SHARING SOLUTION: Scope 3 GHG emissions - Together for Sustainability (TfS) (tfs-initiative.com)

European Commission, “Green Deal: New Proposals to Make Sustainable Products the Norm and Boost Europe’s Resource Independence,” 30 March 2022: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_2013

World Economic Forum, “The Data-Driven Journey Towards Manufacturing Excellence”, 2022: https://www.weforum.org/ whitepapers/the-data-driven-journey-towards-manufacturing-excellence.

OECD Legal Instruments, “Decision of the Council on OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprise”, 2011: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0307.

OECD Legal Instruments, “Recommendation of the Council on the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct”, 2018: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0443.

Allen & Overy, “Towards Mandatory TCFD”, 30 April 2021: https://www.allenovery.com/en-gb/global/news-and-insights/ publications/towards-mandatory-tcfd.